Ultimate Cross Country – Part 1

by Steve Mayotte

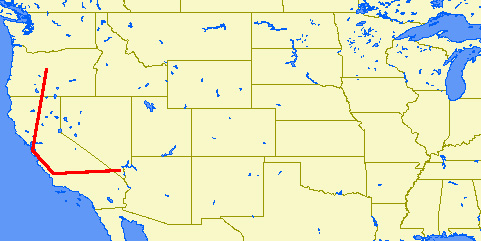

Chapter 1 Route: Redmond, OR to Jean, NV

Flying across the United States is sometimes called “the ultimate cross-country”. Most pilots have considered it. They go someplace nearby and wonder, “What would it be like if I just kept going?”

Since obtaining my certificate back in 1979, the ultimate cross-country siren song has always been within hearing range. Like most folks, I often chose to ignore it. I got married, bought a house, and had children. Short of money, I gave up flying in 1986 to pursue “sensible” ground-based goals.

My Dad passed away in May of 2000. I wrote and presented his eulogy. As I worked to understand his life, I came to better understand my own. Later that Summer, I traveled by air to Philadelphia on business. The trip home took us low over terrain I recognized. The pure and overwhelming joy of flight was rekindled and I started to look into getting current.

I purchased a simulator for my computer. Flying was still natural, but my instrument scan was nowhere. I got my Class 3 medical certificate. That was humbling. Not only am I older than I used to be, I’m also blinder, shorter, and fatter.

I returned to the air on October 25, 2000. My radio procedure was as rough as a cob and I wasn’t sharp, but to my delight, I could still do it. My instructor wouldn’t sign off on my BFR (Biennial Flight Review) and I didn’t blame him. I went home and redoubled my efforts on the simulator. Two weeks later, it was a different story. We flew a brand new Cessna 172. The airplane and I “were one” and I was back!

The next day, I soloed in a Cessna 150 for the first time in 18 years. The significance of the event was not lost on me. Twenty-one years earlier, as a student pilot, I soloed in an almost identical 150 at the same airport. It was déjà vu all over again. Then and now, my thoughts were the same, “Don’t crack it up. Don’t crack it up.”

During the time I was getting re-certified, I prowled the Internet every day looking for a Cessna 150M to call my own. That’s what I learned on. As I looked back in my logbook, all my best flights took place in 150s.

Cessna built the first 150 in 1959. The 150M was built from 1975 to 1977. The Ms were the last of the 150s before the 152 took its place. By then, the panel had what we now think of as the “standard” layout, and the airplane had accumulated years of subtle improvements. To me, the 150M is rakish and modern. The older ones seem like Model Ts.

After having torn my house apart and rebuilding it, I decided that a “basket case” 150 wasn’t for me. I found some beautiful restorations that I couldn’t afford. I also wasn’t looking for a full IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) panel. I wanted a VFR (Visual Flight Rules) airplane with a decent interior, a good engine, and nice paint. Naturally, the price had to be right as well.

With the Internet to help me, I dealt with folks from all over the country. I looked at planes from Virginia, Maine, Texas, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, and Ohio. I found a nice plane in Oregon, but initially ruled it out. That quad combination of the right price, engine, interior, and exterior proved to be tough. As I became smarter, ruling out planes became easier. It took quite a few weeks, but I ultimately ruled out every available aircraft—except the one in Oregon.

Even by a great circle, Redmond, Oregon (RDM) is almost 2,400 nautical miles from my home airport at Nashua, NH (ASH). No matter how you slice it, that’s far! A series of little bumps called “The Rocky Mountains” also stand in the way.

The owner of N714JN (a 1977 150M), Bob McFarlane, and I started a long series of emails. Even though I wanted a plane, in a sick kind of way I was hoping to find a fatal flaw that would rule out this madness. I couldn’t find one.

I ordered the sectionals between “here” and “there” to see what I was getting myself into. After a time, the distance wasn’t problem. It was almost an advantage. The “ultimate cross-country” would be mine if I had the nerve.

Bob and I agreed on a price and the conditions that would allow me to bail out if the plane wasn’t all that he claimed. At once, I felt sick to my stomach. The excitement was palpable, but so were the doubts. What had I gotten myself into? I had only felt this sick twice before—the day I got married, and the day we put a down payment on our house. Both events changed my life, and both turned out fine. Hopefully, purchasing Seven One Four Juliet November would be the same.

Most of the negotiations were done quietly. My son Thomas (age 12) knew what was going on. Because of his keen interest and his low weight, he was the obvious co-pilot. My daughters, Samantha (8) and Caroline (7) simply didn’t believe it. My wife Barbara was in about as much “denial” as is humanly possible.

I spent one Saturday morning ordering airline tickets. Barbara laughed it off. When the tickets arrived in the mail, everyone suddenly knew I wasn’t just talking. The adventure of a lifetime was actually happening.

The court of public opinion was now in session.

One camp (mostly Barbara’s friends) viewed this as a sure-fire suicide mission. They offered advice like making sure my life insurance was paid up. In their minds, I was already splattered high in the Rockies. Many of my friends thought that while buying a plane was OK, “flying it that far is nuts”. Some wondered if I could have it delivered. A few visionaries saw the big picture. Having the plane delivered was unconscionable! They heard the siren song.

Meanwhile, our home computer and a rented 150M became “The Temple of the Expanded Mind” for Thomas. We flew for real and we flew virtually. We worked on actual flying, terminology, navigation, and crew coordination.

I purchased almost every sectional chart available. I ordered the complete set of airport and facility guides. Given any likely weather situation, I wanted plenty of options. I poured over the charts and books, and planned 3 separate routes home. I arranged for a tie-down and for insurance.

The weeks leading up to Christmas 2000 were agonizing. The endless waiting for Santa that most kids can relate to, was nothing in comparison. I anticipate Christmas as much as the next guy. This time, Christmas was an “also ran”. It was endured so that Thomas and I could get to December 26 and the start of our adventure.

Step One of the big plan was to get to Redmond, Oregon.

Thomas and I departed from Manchester, NH (MHT) at 0910. The flight started with some moderate turbulence. A woman seated next to me would have ejected if that was an option. Every jiggle wound her tighter and tighter. “No worries,” I told her. “How do you know?”, she asked suspiciously. I told her I was a pilot, but it didn’t seem like she believed me. Moments later, the air smoothed out. She didn’t say anything, but was obviously relieved.

We landed at Detroit and a bit over an hour later, departed for Seattle. Along the way, we flew over some very cold and deserted places. Even before flying it, my decision to take a southerly routing on the way home looked like a good move.

The third leg of our trip took us from Seattle to Redmond. A very unhappy baby made the start of this trip miserable for everyone aboard. We landed just before 1700. In one sense, getting that far, that fast, was amazing. On the other hand, we’d been traveling for 13 hours and it seemed like it. “Are we there yet?”

We grabbed a rental car and headed for the opposite side of Roberts Field. We found N714JN, but it was getting dark and it was locked. We’d have to wait until tomorrow.

Day 1 – Wednesday December 27, 2000

Due to the 3 hour time difference between home and Oregon, I expected to wake up early. I wasn’t disappointed. I slept late for me—0630 Eastern time. Unfortunately, that translated into 0330 Pacific time. Tom woke up early too. We got dressed, and with nothing else to do, we decided to drive around and see the place.

Seeing Redmond only took a few minutes. We set off for the nearby town of Bend. That killed another 1/2 hour. One the way home, we got lost. But even that didn’t burn up much time. Bob McFarlane was supposed to call us and treat us to breakfast.

We went back to the hotel and waited. At 0700, I called him. Breakfast was out. He had gotten sick over the holidays. He recommended a place called Mrs. Beasley’s and agreed to meet us at the airport at 0830.

Tom and I arrived a bit before 0830 and met Bob. He was taller than I expected, but his real-life persona matched up with his email. [He and I had arranged this entire venture via email!]

After some small-talk, we headed outside to have a look at N714JN. It was a beauty as I had been led to believe. But it wasn’t perfect. The most glaring problem was the missing turn coordinator. It had been replaced with a very old needle and ball. The original artificial horizon had been replaced with a used unit only a few days ago. I didn’t like it. The color was wrong. The clock was broken. The compass window was very yellow. The original dash had been replaced with a decent copy, but the original labels were gone. They’d been replaced with some very lame stickers. The remote control for the ELT didn’t work.

In a sense, I was crushed. On the other hand, this machine was 23 years old. The interior was great, the paint was great, and the engine seemed fine. The fact that we had traveled 2400 miles to see it obviously affected me. I didn’t want to go home empty-handed. I figured that I had at least 95 percent of what I was looking for.

Tom and I loaded up our gear for a short test flight. I didn’t exactly have a test plan. I felt as though I knew what a 150 should be like and I’d just mentally compare this one to what I had flown recently.

It started right up. That was a good sign.

Getting lost at strange airports is always a concern. The folks in the Redmond Tower got me to the active runway.

At 3077’ MSL, Redmond isn’t in the clouds, but it isn’t at sea level either. 4JN blasted ahead, but used more runway than I was used to. I rotated at 60 knots and we turned towards Bend (S07, roughly 10 NM south). I guess I expected Oregon to be lush and tree-covered. The terrain was more like a high desert. Whatever you call it, it didn’t look anything like home.

Everything on 4JN seemed to work OK. The intercom was excellent. Perhaps the VOR was a bit twitchy. That replacement artificial horizon was shaky. The landing at Bend wasn’t my best, but nothing was damaged.

We departed and headed for Prineville (S39, about 17 NM to the northeast). 4JN wasn’t exactly peppy. The engine didn’t seem to be making rated power. I attributed that to the altitude. My frame-of-reference was all wrong. At home, I normally cruise around at 1500’. Around here, it was more like 4500’.

The landing at Prineville was OK and we headed back to Redmond. The tower helped me find my way back to the ramp and 4JN was secured.

Tom and I went inside to find Bob. I extended my hand, “We’ve got a deal.” He was genuinely surprised. He saw us tie the plane down and figured we didn’t want it. Nope. The ramp was on an angle. I didn’t want MY airplane rolling away.

Bob and I passed papers quickly. Because I was paying with a check (safely stored in an envelope marked “The Dough”), there was a surprising lack of paperwork. Bob agreed to mail some extra parts, the wheel pants, and the logbooks to me. As it was, full fuel, our luggage, Tom and I, took 4JN slightly over gross.

Bob gave me the keys, we shook hands again, and that was it. He and I had conversed by email everyday for almost 2 months. I had hoped to have dinner with him or something. It didn’t happen. That was sad.

Tom and I went back to the hotel and checked out. We grabbed lunch, gassed up the rental car and returned to the airport.

We loaded our bags into the luggage area. I couldn’t believe it. “I own an airplane. I’ve flown it exactly 0.9 hours. My only son and I are going to fly across the entire United States.“ Folks have called me crazy before—now it was confirmed. We gassed up, double-checked everything one more time, and headed out.

At 1239, the runway at Redmond left our wheels and the adventure of a lifetime was legitimately underway.

Despite its overall scale and its reliance on GPS, my plan wasn’t too dissimilar from something that a rookie student pilot would put together. Whenever possible, I wanted to follow roads. I had every confidence that my new plane wouldn’t fall apart. The engine, on the other hand, concerned me greatly. It hadn’t been used much in the past 6 months or so. That would change—big time.

Flying the roads is as old as flying itself and it worked great.

We headed south and followed Route 97. A railroad track followed the road. Every time the two of them crossed, we had a rock-solid checkpoint.

At 1336, Chiloquin Airport (2S7) came into view and Upper Klamath Lake soon followed. I had been warned to be careful near the Klamath Falls airport (LMT) and gave it a wide berth. The advice was good. We heard radio calls from a pair of F-15s. Oregon was soon behind us, and we continued into California.

At 1428, we crossed over Butte Valley (A32). At 14,162’ Mount Shasta was impossible to miss. We flew right next to it. I forget our exact altitude, but the top of Mt. Shasta was almost 2 miles higher than we were flying! The pass we flew through was tight. At one point, I asked Tom to “check the clearance on your side”. The wind was light, and the visibility was great. Simply amazing!

At 1458, we passed Dunsmuir-Mott (1O6). Soon after, the chart changed from various shades of orange to the more familiar (and comforting) shades of green.

We touched down at Redding (RDD) at 1529 to refuel. From the Hobbs meter perspective, we’d just flown 3.0 hours. It took 19.6 gallons to refill the tanks. Almost all of that leg was flown with the throttle wide-open. That’s a bit more than 6.5 GPH. Thanks to what Tom calls “unfriendly wind”, roughly 230 NM passed at 76.7 knots. Oh my. Home is far.

We departed at 1550 and continued south. This time, Route 5 provided the guidance.

Red Bluff (RBL) passed below us and we switched to the San Francisco sectional. I was tempted to throw the Klamath Falls chart overboard, but resisted.

At 1629, we stopped for the day at Willows-Glenn County (WLW) airport. While on final, another aircraft wondered if I was from Boston. “Pretty close”, I answered, “Why?”

The voice responded, “You have such an accent!”

Indeed? It made me want to park my plane at Harvard Yard and drink a frappe in my parlor. [The previous line is much funnier if you imagine Ted Kennedy saying it.]

Tom and I tied the plane down and headed into the airport office. Actually, it was the county animal control office. In my defense, it looked just like an airport office. The woman behind the counter offered to give us a ride to the motel (about a half mile away) if we could wait until she closed up for the night.

We squeezed into a small pickup that had seen better days. For example, on the passenger side, you needed to roll down the window and use the outside handle to escape. But no matter, it was free. She dropped us off at the local Super 8 and we settled in for the night.

Day 2 – Thursday December 28, 2000

This was to be our first full day of flying. It started with a long walk. The airport looked close, but it must have been nearly a mile away. It was a lot colder than I expected (probably in the upper 30s). Burdened down with our gear, the airport was far. We dumped our stuff into the plane and continued walking to Nancy’s Airport Cafe, a local truck-stop place that borders the airport.

The waitress was tough, but the food came out quickly, and it was delicious.

After topping off our stomachs, we grabbed the plane and topped it off at the 24 hour self-serve pump. It wasn’t too eager to start. The primer was really stiff and didn’t seem to be working correctly. Still, we got the propeller to rotate and departed at 0711.

Flying at just 1000 feet above the farms, it was glorious. There wasn’t another plane in the sky. A bit over an hour later, at 0822, the Golden Gate Bridge slipped beneath our wings. It was clear and beautiful. The San Francisco Terminal Control Area thoughtfully allows unfettered flight in this neighborhood. Bob McFarlane later told me that he’s flown over the GGB a bunch of times and has yet to see it.

By now, the air temperature was in the low fifties and we opened the air vents. It was seriously winter when we left home. The sweet smell of Pacific Ocean air was amazing. One of my goals was to fly “coast to coast”. Well. One coast down, one to go.

At 0836, we stopped at the Half Moon Bay (HAF) airport. The surrounding terrain was lush and green. It was a shame we didn’t have time to dally. After a short bathroom break, we departed at 0902 and continued down the coast until over Watsonville (WVI) near Monterey Bay.

It was back to road navigation as we picked up Route 101 past Salinas (SNS). Mesa Del Ray (KIC) fell behind us at 1018. By now, the fuel gauges were banging down around “E” a bit more that I like. We pressed on towards Paso Robles (PRB).

My anxiety level was far too high. After all, this was supposed to be fun. I started thinking about the 3 most useless things for a pilot: runway behind you, altitude above you, and fuel you didn’t buy while on the ground. Naturally, the pattern at Paso Robles was filled with everyone and his brother. Given the chance, I would have quietly flown straight in. I reduced power and flew a full pattern—upwind, crosswind, downwind, base and final. At the first sign of trouble, I was ready to declare an emergency. Luckily, we made it and took on 20.0 gallons of fuel. That meant we only had 2.5 useable gallons left at touch down.

That was really dumb. Can you imagine cracking up your new plane on its maiden flight? [Actually, a high percentage of Cessna 150 accidents involved fuel exhaustion.] I survived to learn a valuable lesson. My 150 can be flown for 3 hours without the slightest concern. After that, be prepared to sweat.

At 1121, we left Paso Robles and headed for Tejon Pass near the Gorham VOR (GMN). The original plan had us heading for Bakersfield (BFL), but the fuel stop at Paso Robles made stopping at Bakersfield unnecessary.

This course change was just about spur of the moment. The GPS pointed the way and we followed. It was a bit disturbing to not even have a line on the chart. I struggled to find visual checkpoints but didn’t have much luck.

After about an hour aloft, we noticed that the visibility below us wasn’t so hot. At altitude (around 4000’), it was fine. I was able to pick up the ATIS at Bakersfield. They were IFR with the visibility hovering around 1.5 miles. In essence, we were “VFR on top”. Yes. But on top of what? I spent weeks flight planning, but never considered this situation.

While we weren’t exactly on course, we weren’t lost. We were VFR on top—kinda. What next? Naturally, the engine began to run rough. I tried every kind of leaning, but that didn’t help. Finally, I tried a touch of carburetor heat. Whew! But what’s up with that? I had 121.5 (the international distress frequency) already dialed in on the radio.

Some pilots talk about the “pucker factor”. It’s a reference to how tight your butt is in the seat. I was tight, but doing OK. Then the GPS stopped tracking. Luckily, I’d seen this happen once before. The answer was to totally reboot it by taking out the batteries. That crisis didn’t last long.

Tom and I strained to find Route 5. That was the tell-tale for Tejon Pass. In retrospect, we were more south and west than we should have been. We found some small mountain passes, but they didn’t have a proper sized road. At this point, the GPS was only a guide. Following it’s course advice literally would have had us burrowing tunnels. We were now strictly VFR. Find the road. Don’t bump into the hills.

Without the slightest warning, the engine started to run very, very rough. I remember thinking, “so this is what an engine failure is like”. Damn it! I figured we had broken a valve. There were plenty of places to land, so I knew we were going to live. But I was really mad. My new little plane had failed me!

Once again, carburetor heat saved the day. I have since read that carburetor ice can happen under just about any conditions. I’m here to tell you—it’s true.

Route 5 finally came into view and we climbed into Tejon Pass. Less than 10 miles later, we were in the Mojave Desert. The weather was the very definition of “beautiful”. The folks at the General Fox (WJF) airport [Lancaster, CA] were calling the visibility 50 miles. We touched down at 1310.

We taxied up to the café and shut down. Whew! The past 109 minutes were really something! I was certain that my already graying beard must be white as snow by now.

The café’s menu included “The $100 dollar hamburger”. That sounded swell. The café also sold beer. That sounded GREAT, but I made do with a Coke.

After lunch and a quick re-fuel, 4 Juliet November’s wheels left the ground again at 1411. Our goal for today was the airport at Jean, NV (0L7). Since we were flying to the eastern edge of the Pacific time zone, I knew it’d be getting dark early. We couldn’t have any more of these “navigational uncertainties”.

After departing General Fox, we headed towards 34° 45’ N, 117° 30’ W. That was a coordinate I picked to avoid the restricted airspace associated with Edwards Air Force Base. Next, it was on to the Barstow-Daggett (DAG) airport. We flew over it at 1503. I used the RCO (Remote Communications Outlet) located there to contact Riverside Flight Service. Tom was on the wheel at this point and was following Route 40.

I inquired about the status of the Silver MOA (Military Operations Area). After some obvious searching around, the fellow on the other end suggested I contact Los Angeles Center. This turned out to be quite a challenge. LA Center was very busy. Just getting in a word edge-wise was almost impossible. A complicating factor was our altitude. We were low, so even basic communication was difficult. It took a bunch of tries, but I was finally told that “the Silver MOA is cold” (i.e., safe to fly through).

By now, I realized that the one thing I had wanted to avoid (namely, getting lost) was exactly what had happened. We were supposed to start following Route 15 at Barstow.

Instead, we had been following Route 40 (incorrectly) for almost 30 miles.

A corrective course was easy enough. I pointed the GPS at Baker, CA (0O2). The problem was that we needed to fly over almost 30 miles of nothing to get there. The surrounding terrain made receiving the Daggett (DAG) and Hector (HEC) VORs so-so at best. Periodically, I was able to get a rough idea of our progress. But basically, there was nothing to do but fly the intercept course for what seemed like an eternity.

Finally, Soda Lake, the town of Baker, and the Baker Airport came into view. Route 15 was right where the chart said it would be and we were back in business.

Route 15 is the road to Las Vegas and it seemed like the whole world was driving there. We climbed up to make the pass near Wheaton Springs. From there it was downhill to Jean, Nevada. We landed uneventfully at 1616.

A lighted and paved walkway led us from the airport to the 800 room Gold Strike Casino and Hotel. Just like earlier in the day, what would have been a pleasant little walk was ruined by having to carry our gear.

Both Tom and I have watched more than our fair share of the Discovery Channel. I thought I knew what this place would be like. The Gold Strike is relatively small. The casino is small by Las Vegas standards but really big if you are carrying luggage. Thomas was moaning severely so I had most of the bags. He was wearing his winter parka and looked completely out of place.

Naturally, to get to the hotel, you must walk through 100 percent of the casino. Perhaps it’s fun for some, but I saw an awful lot of crippled-up old ladies apparently feeding their last nickel into the slot machines.

We got a room and headed up to the 14th floor. To my delight, our room overlooked the airport. I collapsed on the bed.

The past 7.6 hours and almost 550 nautical miles had seen quite a mix. Flying over the Golden Gate Bridge, calling out “feet wet” as we flew over the Pacific Ocean, and landing at Half Moon Bay had been great. Nearly running out of gas, almost having our engine quit, and several navigation errors concerned me greatly. This wasn’t exactly our finest hour, but we made it.

It wasn’t “the beginning of the end”, but it was “the end of the beginning”.